Ludwig Wittgenstein’s Beetle in a Box Analogy

Ludwig Wittgenstein was a 20th century Austrian-British philosopher. He worked in logic, the philosophy of mathematics and the philosophy of the mind. He is known for his innovative and confusing ideas regarding the philosophy of language including the nature of language, internal experience and the relationship between them.

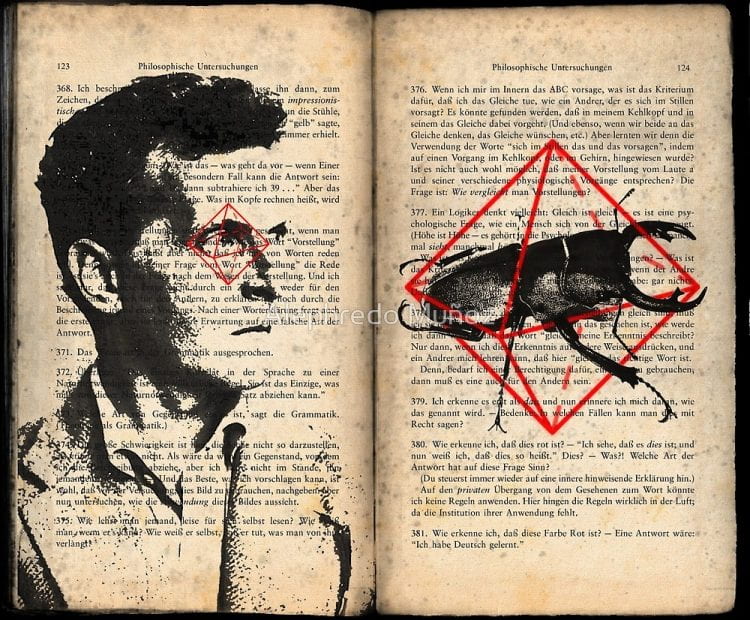

To help illustrate this relationship Wittgenstein proposed the following metaphorical thought experiment in his book Philosophical Investigations – a book considered by many as being one of the most influential philosophical works of the 20th century.

In this experiment he suggested we imagine a group of people, and that each person has a box that only they, and no one else, can see into. They are only allowed to talk about what is inside their box and inside each box there is a thing that everyone describes as a ‘beetle’. I know what a beetle is from my own examination of what is in my box, you from yours.

Wittgenstein points out that while we can talk about our beetles there might be different things in everyone’s box, or even nothing at all, and if there is, can anyone know what anyone else’s beetle actually looks like? Everyone can describe whats in their box using words that everyone shares and understands regarding what’s in their box, which in this case is ‘beetle’. However, according to Wittgenstein the thing in the box cannot be meaningfully talked about using the word ‘beetle’ because no one can confirm what anyone means by ‘beetle’; it can therefore only mean the thing that’s in the box and can’t necessarily describe the thing that’s actually in the box.

Wittgenstein uses this analogy to suggest that the felt states and sensations that occur in a person’s mind, such as smell, pain, happiness and sadness, are things that no one can ever communicate sufficiently enough to share and reveal their experience to others.

As no one knows what is in anyone else’s box, in order to think and communicate about the beetle, the word must be something that everyone understands or can be taught for the word to have meaning. According to Wittgenstein and many others language is entirely social. This theory is known as the private language argument which proposes that the language we use to refer to our private experiences is only formed through when they are shared with other people, and to have language that exclusively describes ones own private experiences is impossible. Therefore, the sensation of something may exist exclusively to oneself but cannot be understood in terms of language exclusively to oneself. This means that we can only assume that other people’s experiences are anything like ours, even if they talk about them in a similar way. Arguably, attempting to rationalise and communicate the mental experience of a sensation becomes inconceivable after a certain point.

For example, someone could say that oranges smell nice but when asked what they smell like they might say ‘they smell sweet’ or ‘they smell fruity’. But when asked what that smells like they might be able to find a few other smells to compare it to but would eventually and inevitably reach the limits of language and there would be no answer to what it smells like. A sensation that no one besides the smeller for sure could know what it is like.

If you were asked to describe what a banana tastes like, or what pain feels like, what would you say?

Referring to subjective experience and that which exceeds language and logical understanding Wittgenstein writes this ‘whereof one cannot speak, thereof one must be silent.’