PIE: The projected progenitor of Indo-European languages

Proto-Indo-European is a very complex language. The language itself is not overly complex, but the method by which it was worked out was extremely convoluted. Work on it is not finished yet, either, for more words, structures, and pronunciations are regularly proposed.

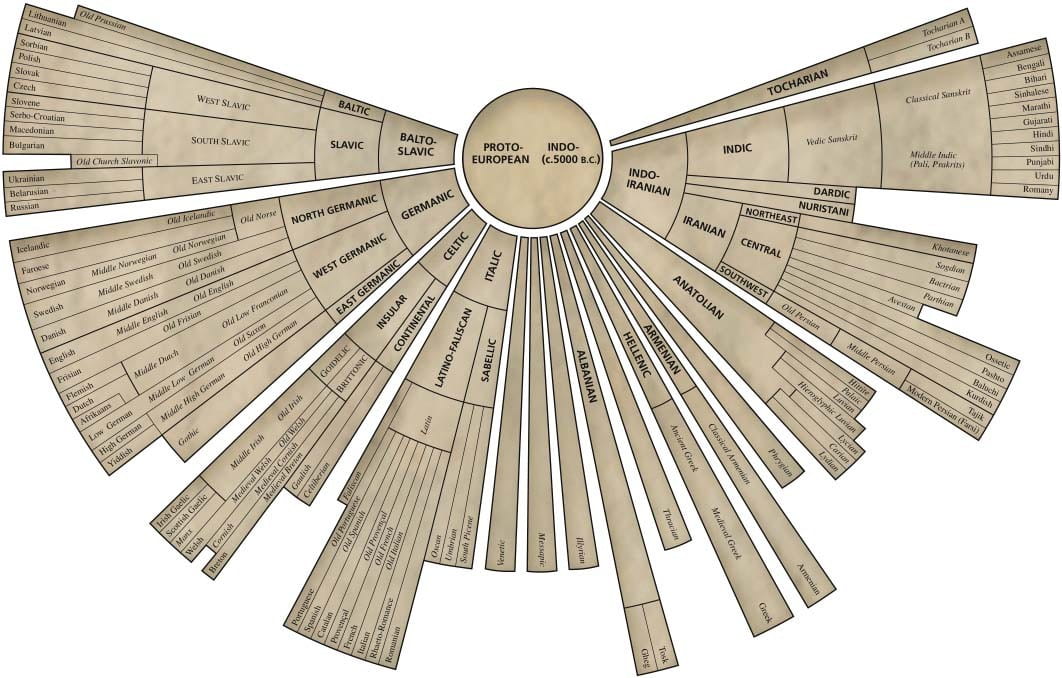

But first, a little background. Proto-Indo-European (henceforth referred to as PIE) was the language spoken by the Neolithic inhabitants of the ‘Pontic-Caspian steppe zone’, which is now south and western Russia and Ukraine circa 4,000 BC. No written record of the language remains, but as most modern European and Indian languages developed from it, the full structure of any such language can be meticulously reconstructed.

By the nineteenth century, linguists and historians had realised that most Indo-European languages had developed from the same, single root. This theory was first publicly proposed by William Jones, an Anglo-Welsh philologist and lawyer, who spent time in Bengal as a judge, and a part-time scholar of ancient India. In a speech delivered to the Asiatic Society in 1786, he suggested that Greek, Latin, and Sanskrit (an ancient Indian language) had a single common ancestor. He then suggested that the Gothic, Celtic and Persian languages may also come from this extinct language. In 1814, the English polymath Thomas Young gave this shared progenitor the name Proto-Indo-European, from the Greek proto, indicating a precursor.

This idea was supported by some, and opposed by others, and some research into it was done over the following few years, though no great leap forward was made. Then, Jacob Grimm (of the Brothers Grimm) came up with ‘Grimm’s Law’, postulating the change of one consonant to another, explaining the regular occurrence of cognates beginning with p in earlier languages, and f or v in later ones. Then, using this insight, August Schleicher attempted to reconstruct the proposed ancestor language and its grammar, based on Greek, Latin, and Sanskrit. Schleicher, a German linguist, had previously used the image of a tree to represent the evolution of language, and had proposed that languages follow a life cycle, similar to that of human beings: they start primitive, but then evolve and grow, and then that growth slows and stops, and then the language decays. His book (which was published to save his students from having to make notes) was titled A Compendium of the Comparative Grammar of the Indo-European, Sanskrit, Greek and Latin Languages, and goes over, in detail, the proposed grammatical system of PIE, and links it to Greek, Sanskrit and Latin. Schleicher also published a reconstructed fable, called ‘the Sheep and the Horses’, to demonstrate how he thought PIE would have looked and sounded. While the plot was made up by Schleicher, it is written entirely in his version of PIE, which is remarkably similar to modern estimations. I won’t include it in full here, but do google it for a full version.

The method by which he constructed his framework for PIE appears, at first, to be simple, but when used to reconstruct an entire language, it became complex and time-consuming. It also requires an excellent understanding of as many languages as possible. To put it simply, Schleicher first grouped languages together into ‘families’. Then, taking all the words that mean the same thing in that family of languages (for example, the cognates father, vater, pére, padre, pater and pitar, the word that shows most clearly both the links between the languages and the shifts of consonant from p to f), and taking into account known vowel and consonant shifts, he worked backwards to ‘ph₂tḗr’ (the h2 merely indicates one of three supposed guttural laryngeal sounds, no longer used in the daughter languages of PIE). Then, he repeated this method for every other cognate he could find, and for the grammar too, to reconstruct the language. His efforts were really quite accurate, when compared to modern computer-assisted estimations.

Subsequent scholars also researched, expanded and emended Schleicher’s work, and wrote their own demonstrative fables in their newer versions of PIE. One, called ‘The King and the God’, is loosely based on a passage from the Rigveda, a book of Sanskrit hymns. At first glance, the whole thing seems to be completely unintelligible, and to an extent it is – no layman could translate it, in full. But many words are near cognates. Take, for example, the word ‘prēḱst’. Now compare it to its modern English translation, priest. Or, ‘súhxnum’, meaning son. But it is not just English where similarities appear. For example, ‘dei̯u̯óm’, (god), and ‘H3rḗḱs’ (king) are very similar to the Latin words ‘deum’ and ‘rex’ respectively. To hear these two fables read, and (roughly) correctly pronounced, in PIE, click here. While there is, of course, dispute between academics on the exact pronunciations and sentence structures that would have been correct, the versions that have been rebuilt thus far would almost certainly be understandable to the original speakers of the language, were there any way to gauge their opinion.

But, you may ask, what is the point of reconstructing this long-dead language since nothing remains written down of it? The answer to that is the same as for any other historical or archaeological research, for the language is an informative remnant of a forgotten civilisation, as useful as any archaeological remains. By reconstructing it and plotting the divergence of other languages from that one root, we can discover many things otherwise lost to history. For example, by tracking the history of the word ‘wheel’, we can indirectly track the history of the wheel itself, and the history of those cultures that used the wheel. It also allows us to work out what the landscape of central Europe was like at that time, for the history of words for plants, animals and geographical features can also indicate when (and where) they were first (or last) encountered. While this information alone may be little more than interesting, it helps us to build up a picture of the ancient world and to plot the course of human history,

Software has also been developed to take a variety of modern words from different languages in the same ‘language tree’ and reconstruct their ancestor. This software is just one character out, 85% of the time, from the word worked out by humans. With a little refinement and further testing, this software may be able to use the techniques learned from the rebuilding of lost languages to vastly improve translation software for modern languages, making google translate a much more effective and useable resource.

PIE is not, however, the only language to have been reconstructed. Proto-Germanic and Proto-Romance, the two daughter languages of PIE which led to the Germanic and Romance branches of modern language, have also been rebuilt from both PIE and our knowledge of early and vulgar Latin and of the history of modern languages. Other languages, unrelated to these have also been reconstructed, from the Proto-Miwok of ancient California to the Dene-Yeniseian, the precursor of the languages of central Siberia. But the work is by no means finished, as there are a number of languages that are known but not yet rebuilt. Most prominent of these is Etruscan, the precursor to Latin. Much is known about this language, both grammatically and in terms of the vocabulary, but no full reconstruction has yet been managed. There is much desire to decode the language though, for some thirteen thousand inscriptions survive in this lost language, and who knows what information may be hidden in this ancient script.

All in all, Proto-Indo-European, and the other reconstructed languages, are worth the huge amount of effort which is put into them, both for the historical and archaeological returns they provide, and for their modern benefits to computer algorithms for the translation of modern languages.