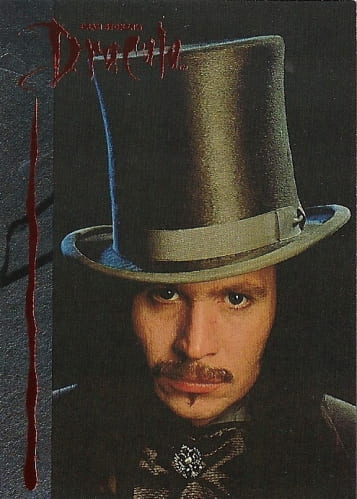

Duality in Dracula and the other Gothic Texts

Throughout history, duality has evolved, changed and regressed with the events of the time and the social setting of the reader. Texts from the Victorian era such as Bram Stoker’s Dracula and Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein highlight the transition from a society mainly basing their beliefs in religion to the technological advancements and growing following of science; more modern authors such as Angela Carter and The Bloody Chamber Collection play with and provoke the fears of our childhood (e.g. Having a fear of darkness) and using this to terrify its readers psychologically. Gothic authors often use the current affairs of the time of their writing to create a more real and immersive environment for their readers, and with the combination of duality on these themes, conjure tales that remain popular and relevant for many years afterwards.

One of the first duality combinations commonly seen in Gothic texts is that of science versus religion or superstition. As Dracula was written towards the end of the Victorian age of enlightenment and industrialisation, there are many links which Stoker uses to show the conflict between the popular and more archaic Victorian ideals of a Christian household and the growing movement of science (such as the discovery of electricity and Darwin’s evolutionary concepts). As a scientific and logical man of modern-Victorian Western society, Jonathan Harker is first portrayed as a straight-laced gentleman with little regard for the beliefs and warnings of the ‘lesser’ and ‘uncivilised’ people of Romania – when he is warned by one of the ladies of the village, he simply says to the reader that “it was all very ridiculous […] as an English Churchman, I have been taught to regard such things as in some measure idolatrous”, going as far as to ridicule her for her superstition. His perspective changed later on, however, when he has come to know the Count and encounter all sorts of unnatural and taboo happenings – “my feelings changed to repulsion and terror when I saw the whole man slowly emerge from the window and begin to crawl down the castle walls”; he has lost all concept of science and logic that he originally had, and acts as a parallel first-world gentleman for Dr Seward. At first, Seward believes that Lucy’s teeth look sharper “by some trick of the light” but later on begins to accept the supernatural when he thinks he sees a “white streak” out in the graveyard. The Victorian reader would be caught in the middle of the two beliefs – whereas the wonders of electricity and science were bringing back to life those such as Mary Shelley’s monster in Frankenstein, superstition and the ‘un-dead’ appeared omnipotent in the face of death in Dracula.

The conflict of science and religion are shown in a slightly different way in Angela Carter’s The Bloody Chamber. Written for an audience where religion and superstition were becoming increasingly less popular and science was the main belief system, these tales are subverted more to the fairy-tale genre, taking us back to the fears and possibilities suggested in our childhood. This may be because the “Gothic castles, villains and ghosts already made clichéd and formulaic by popular imitation, ceased to evoke terror or horror” as the critic Botting said, or maybe because Carter’s more egalitarian subversion of the popular tales allowed a new and exciting angle for the readers. With Carter’s focus on the fairy tales, there is a mixture of science turning to superstition and vice versa, for example the ordinary girl as protagonist in the titular story who gains a supernatural red mark on her forehead from the Marquis, compared to Wolf-Alice, whose belief in the patterns of the moon and her fellow wolves biting her (“a wolf, perhaps, that was fond of her, as wolves were, and who lived, perhaps, in the moon?”) turning out to be her menstrual cycle. Where in Stoker’s tale the distinction between science and supernatural is more prominent, the line between the two opposing sides is much less clear in Carter’s stories, and so the reader is drawn in by the intrigue of the now-unfamiliar superstitious beliefs, tales and concepts such as the Erl-King, who would be unknown to an American or British audience reading the story of ancient German folk-lore. In Robert Louis Stevenson’s book The Strange Case of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde, the audience is exposed to the possible realities that science could bring, and the dangers and unknown factors that came along with that (a scare for an audience whose beliefs still lie in that of body and soul, but also has the growing confidence in science and technological progress). Where there are some parallels in the nature of science versus superstition in both The Bloody Chamber and Dracula, there are also opposites and blurred lines – it is clear, however, that a conflict between science and superstition is common in most Gothic texts, especially in those from the Victorian era and onwards.

Another literary interest the Victorians had was that of travel. With industrialisation just beginning, the Victorian age was the start of travel becoming more accessible to everyone, although still a little limited and more risky than our ability to travel today. When Jonathan Harker travels to the unknown lands of Romania, he both gives a factual account of everything he sees in order to tell the population back home, but also puts forward his very western view of other more ‘primitive’ civilisations. Just the opportunity for Harker to travel abroad would entice a Victorian reader to continue with the story, but the duality of this opportunity compared to the entrapment he faces when he reaches his destination invites them to read further. The castle, home to the ‘civilised’ nobility of that foreign country – the place where he should have felt most at ease in his disposition – became his “prison”, and the “lofty steeps of the Carpathians […] bringing out all the glorious colours of this beautiful range” serve as the barrier between him and his freedom. The critic Botting writes that “in crossing the borders between East and West he undoes cultural distinctions between civilisation and barbarity, reason and irrationality, home and abroad”, which fits in with the Victorians’ fear of the unknown and the international hierarchy in which they feel superior. In contrast, Angela Carter’s settings for her stories vary, but all have the common theme of anonymity. The unknown and unspecified area allows the reader to use their own imagination instead of being informed of what other places are like, and can more easily serve metaphorically as the labyrinths and hidden places of their own minds – the fear of being trapped inside ourselves, a fear that has grown from a society needing to know their own true identity. For example, the castle in the titular story could serve as the Marquis’ own mind palace, including the room in which he mutilates and destroys women, physically and sexually; the “subtle labyrinth” of the forest in the Erl-King could act as the labyrinth one has to find the way through in order to discover oneself. Both stories carry the idea of intrigue in the exploration of new and foreign places, accompanied by the entrapment of the protagonist (at the time in Dracula’s case), but have simply changed due to the evolution and psychological needs of society.

A common theme in the Gothic trope is the progression from innocence to corruption. Chivalry was still common gentlemanly behaviour in the Victorian era, and women were viewed more as valuable objects and trophies rather than having any direct impact on everyday society. In Dracula, this is still largely the case, until the corruption of the ‘innocent’ Lucy turns her into a dangerous vampire – the naïve girl who wished she could “marry three men, or as many as want her” turns into a “voluptuous wantonness”, not only having the power of beauty to capture men but also the supernatural strength and seductive nature of a vampire which can kill them. Jonathan Harker, on the other hand, is corrupted more in the mind than Lucy’s physical change. After his experiences with the Count, most people assume that he simply has “brain fever”, a slight sort of madness that was not there before. In reality, his belief in science alone led him to be corrupted by the things which science cannot explain, for example, Dracula’s control over the wolves. Harker believes that science has an answer for everything, and thus in believing so, he begins to drive himself mad until he accepts abstract concepts such as vampirism and fate. Angela Carter’s stance is generally much more physical in the corruption of innocents – the girl in The Snow Child is brutally raped after death, and the Countess’ body in The Lady of the House of Love ages and degrades after she changes from the innocence of sucking blood to the one being leeched. There are some mental changes, such as the girl in The Company of Wolves and the acceptance of the girl in The Tiger’s Bride, but these are much more subtle in comparison to the more raw sexual corruption in the rest of Carter’s stories. In comparison to Dracula, The Bloody Chamber seems quite similar in its mixture of mental and physical corruption, but where Carter’s sexual references and implications are quite blunt, those in Dracula are more subtle – for example, where Carter says ‘a dozen husbands impaled a dozen brides” in the titular story, Stoker uses the phallic image of the stake and the ecstatic fits in Lucy’s sleep to symbolise the female orgasm. These concepts fit very well with the reception of the time, as the straight-laced Victorians would have enjoyed the subtly of such symbols (along with how “Dracula acts out the repressed fantasies of the others”, as Phyllis Roth said), whereas the late twentieth-century audience of Carter’s book would have been intrigued by such bold statements of sexual desire and potency.

Another common theme in Gothic literature is the contrast between light and dark. With the electric lightbulb invented only a few years before and superstitious fears becoming more prominent in times of darkness, Stoker utilises this to present darkness and the night in general as the time for all fears and horrors to be unleashed. Dracula is seen by Jonathan late at night (he confirms this later and says that “this diary seems to be horribly like the beginning of ‘Arabian Nights’”) and the blue lights marking the places of buried treasure only appear at night. Lucy’s fits come on during the night, and terrifies her to the extent that she does “not want to sleep […] ‘sleep was to [her] a presage of horror’”. In contrast, a large number of Angela Carter’s tales occur during the day – for example, the Marquis “[cuts] bright segments from the air” with his sword, implying the bright sunlight around them. Carter’s focus lies more in the pathetic fallacy of the texts – some of the stories, such as The Courtship of Mr Lyon and The Company of Wolves are set in harsh weather such as snow and ice, and Carter uses this to demonstrate the dark meaning rather than using the night as Stoker does (for example, Puss in Puss-in-Boots “[breaks] into impromptu song at the spectacle of the moon”, quite the opposite to the sudden appearance of Dracula’s grim wolves). This may be to do with the reception of the texts – whilst we in modern times have overcome the fear of the dark that still reigned strongly for the Victorians, we today fear much more the possibility of horror and terror being thrust upon us, no matter who you are, at any time. The critic Steve Roberts puts this nicely into perspective when he says “Dracula embodies the fear of the unknown and he personifies the ‘nothing in the darkness’ that keeps children awake at night”. The duality of lightness into dark can be shown metaphorically in both texts also – Lucy and Mina’s corruption shows the ‘light’ of beautiful innocent women turning to the dark of the brutal un-dead in Dracula, and those such as the girl in The Courtship of Mr Lyon have their lightness (“absolute sweetness and absolute gravity”) turned into darkness in the discovery of their own beauty and power (“instead of beauty, a lacquer of invincible prettiness that characterizes certain pampered, exquisite, expensive cats”). The metaphorical darkness is not so heavily emphasised in Carter’s tales, as her dark emphasis lies more in corruption itself, whereas Stoker’s focus is more on the darkening of the soul, turning life into something not quite dead, yet not humane enough to be alive.

The Gothic genre is filled with duality and transition from one mind-set to another, whether it is the belief in science to superstition, or light into darkness. Duality has played a huge role in Gothic texts, ranging from those written in the early 19th century to those still being written today. The purpose of duality in the Gothic ranges: it can be to evoke fear into the reader, to create psychological terrors or just simply to draw the readers’ attention to their startling concepts. Bram Stoker’s Dracula and Angela Carter’s The Bloody Chamber Collection are perfect examples of the use of duality in an effective and sustaining Gothic text, still taking into account that the duality is different in each text. There are common themes in the dualities of the two books, and a comparison can be made that draws these two books together, in that the writers catered to the needs of their audience of the time, and the impact this made on those people allowed the text to remain part of popular culture for many years afterwards.

Rosie Harvey 12ADS